Taking notes in interviews

One of the common pieces of feedback to my previous article arguing against panel interviews was that folks found it difficult to interview and take notes at the same time. Having two interviewers makes taking notes much easier: one person can interview while the other takes notes.

This is certainly true, but I’m not sure the value of easier note-taking outweighs the problems that multiple interviewers introduces. Mostly, this is because I don’t find taking notes while conducting an interview particularly difficult. I know that people differ, and that what’s easy for me isn’t always easy for others. However, I do wonder if the folks struggling to take notes during an interview are approaching note-taking as effectively as possible. Like anything, note-taking during interviews is a skill that can be learned, and there are approaches and techniques that make it much easier.

Techniques for effective note-taking in interviews

Let’s explore those techniques by working through the common problems that interviews face around note-taking:

Problem: it’s difficult to take notes while carrying a conversation.

Solution: talk less1.

Good interviews are conversational, but they’re not a conversation! If you’re struggling to take notes and also carry a conversation, it’s worth asking if you might be talking too much. As an interviewer you should be trying to talk as little as possible; you want as much of the hour to be spent listening to what the candidate is saying. Yes, you need to ask follow-up and clarification questions, but those should be very short and to the point. You don’t need to be thinking about your next question as the candidate talks: follow-ups should be written down in your interview guide (more on this below). You can simply listen, and take notes.

It’s fine to take a moment as a candidate finishes to capture some notes. Don’t be afraid of 10-15 seconds of silence. It’s also totally fine to say something like “thanks, that was good, give me a minute to write that down” if you need a bit longer. The mild awkwardness this introduces can be easily mitigated by saying this with a friendly tone.

Problem: it’s difficult to judge a candidate’s answer while interviewing and also taking notes

Solution: capture data during the interview; analyze later.

When I was talking this topic over with Sumana, she told me she has two very different styles of note-taking. The first is capturing what was said without any value judgment, e.g. taking minuets at a meeting where she’s not an active participant. I like to think of this as “stenographer mode”: capturing what was said, but not passing judgement or analyzing in any way. She contrasted that with trying to take notes while working with her coaching clients, where she’s actively listening, analyzing the pros and cons of what her clients are proposing, and thinking about how to follow up with more coaching prompts – all while trying to capture notes!

That’s much harder. Trying to take notes while also engaging critically with what your counterpart is saying is significantly more difficult than merely listening and capturing what was said without analysis.

During the interview, be more like a stenographer. You should be capturing notes on the candidates behavior – what they told you, what they said, how they said it – but not yet trying to draw conclusions. During the interview itself all you’re doing is data collection. You’re capturing all the information the candidate is giving you, but not really thinking about it yet. Data analysis comes later, after the interview; at that point, you review your notes and start to make some conclusions.

Problem: I can’t write fast enough to capture everything a candidate says!

Solution: don’t try!

Please don’t interpret “stenographer” literally: your notes are nothing like a transcript. You don’t need to literally capture everything that was said. Quite the opposite. In fact, your notes only need to be sufficient to help you to recall the interview afterwards, no more.

Interview notes are your personal work product; they aren’t something you’ll share. You’ll later share a summary and your conclusions, but your notes absolutely don’t need to be comprehensible to anyone other than you. Figure out the absolute minimum you need to write to jog your memory a few hours later, and skip writing the rest.

Nor do your notes need to be captured for posterity. You you should be doing your data analysis pretty quickly after the interview – immediately after the interview, if possible, and within 24 hours at the most. Thus, you only need whatever notes are sufficient to recall the interview when it’s still relatively fresh in your mind. Once you’ve read back through your notes and drawn your conclusions, you can toss your notes2.

The secret to efficient note-taking: print, and take notes on, your interview guide

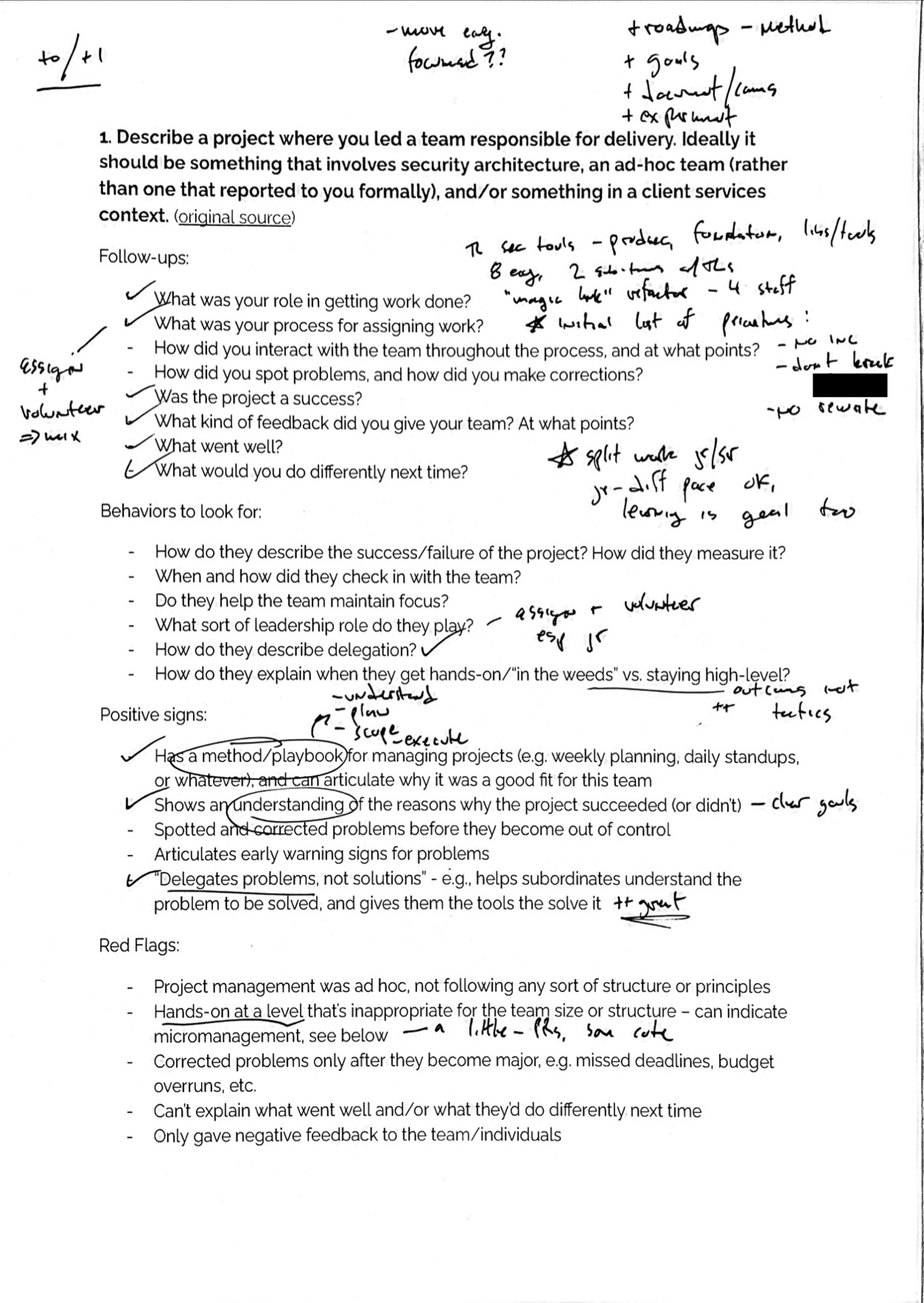

Let’s bring this all together by looking at an example page of notes from a recent interview I conducted3 (If you’re interested in more about this question, it’s a variation of “Tell me about a project you led…”, which I wrote about last year).

If there’s a “secret” to efficient note-taking in interviews, you’re looking at it. I recommend that you print out your interview guide and rubric, one question per page, and take notes directly on that printout.

If your questions and rubrics are sufficiently detailed – see my interview questions series for examples of the level of detail I think is appropriate – lots of your note taking can be as simple as checking off behaviors/signs written down on the rubric. Notice how I’ve done that above: notes tend to be physically next to the parts of the rubric they refer to. For example, under positive signs, I’ve circled “understanding” in “shows an understanding of the reasons why the project succeeded”, and next to that written “— clear goals”. This reminds me that I asked about what the candidate thought led to the project’s success, and they highlighted having very clear goals from the outset so that they could recalibrate if they started moving away from those goals.

This practice lets me be super-efficient with my note-taking: I’ve written only a small handful of words, but those words, in the right place, along with the underlines and circles, are enough to help me recall the question. There isn’t enough here for anyone else to reconstruct our conversation, but even a couple months later, I still recall this candidate and their answers.

Having the guide in front of you this way also means you’ll also have follow-ups and points to probe into right there in front of you. This means you don’t need to be thinking about what to ask next too much; just look down and consult your notes. Notice in my example that I’ve ticked off the follow-ups I asked to keep track of where I’ve probed (and where I haven’t). I can recreate what we talked about through a combination of the notes I wrote and the follow-ups I ticked.

Taking notes this way also forces you to take notes longhand on paper (or a paper-like device like an iPad or Remarkable). Many people find that this aids in retention; indeed, some studies have found that taking notes longhand leads to better retention than when typing. Further, typing while a candidate talks can also be distracting to the candidate. For in-person interviews, typing at your laptop while a candidate talks can feel rude; the social norms around looking at screens can make it feel less respectful than handwriting notes. And for remote interviews, the clicking noise while you type can be distracting.

I like to print out the interview question and rubric itself, one question per page, and take notes directly on that page.

Now, I should point out that my example isn’t perfect. There isn’t enough room on this sheet for lots of notes, so mine are crammed into the margins. Likely these notes are a bit more terse because I didn’t have enough space. I usually aim for the rubric to cover only about half the sheet, so I have plenty of room. I should bump the font size down (or something) so I have more room for notes.

Drawing conclusions after the interview

You’ll also notice what look like conclusions at the top of the sheet – I’ve written “+0/+1”, and some positive/negative points. That’s the last part of my note-taking practice, so let’s talk about drawing conclusions from your notes.

First: remember what I wrote about: you should try to avoid drawing conclusions during the interview. (Yes, I have what look like conclusions on this same sheet – I’ll get to that in a moment.) This is hard: we’re human, and used to making snap judgement; we almost can’t avoid it. It’s not unusual to find yourself thinking “we should (or shouldn’t) hire this person” within literally the first sixty seconds of an interview. This is the other huge reason to focus on capturing behavior (and not conclusions) in your notes. If your notes are strictly what the candidate said and did (and not your interpretations), you can review those notes after the interview and draw a conclusion deliberately, less colored by that initial knee-jerk response4.

So let’s return to the top of my notes sheet. Aren’t those conclusions? Kind of, but:

- I probably wrote this after the interview, during the data analysis phase. That’s what I should have done, at least: after the interview, go through my notes on each question and note their performance. But I’m not a perfect practitioner of my own advice: sometimes I do make these notes as the candidate finishes answering, and I can’t tell exactly what I did here. This is mildly dubious, but …

- What you’re seeing is a first pass, not quite a conclusion yet. I’m summing up how I think the person performed on this question, but still not an overall “hire/no-hire” conclusion. I’m noting a quasi-score ("+0/+1")5, and some high/low points. That makes it feel acceptable to note down a score like this in the middle of the interview: performance on any single question isn’t usually the deciding factor, so I’m still holding off on making a conclusion until later.

Finally, once I have a score for each question, the final step is to go through all of the questions, look for themes and patterns, and draw an overall conclusion. That conclusion will be of the form “we (should or shouldn’t) hire this person, and here’s why…” – and I’ll write more about that in my next article. Stay tuned!

I usually end up keeping my notes for a couple of weeks, but only because that’s the frequency at which I clean my desk. When I do my roughly bi-weekly “oh dang my office is a mess” panic-clean, I’ll shred any notes older than a couple of days. ↩︎

These are actually a recreation made while looking at my original notes and transcribing most of them on to a fresh sheet. The original notes had a bit more identifying information on them, so I transcribed (and still ended up needing to redact one thing). ↩︎

Folks who have read Thinking, Fast and Slow will recognize these two modes of thinking as what Daniel Kahneman calls System 1 (fast, emotional, intuitive) and System 2 (slow, deliberate, logical). Hiring decisions should be System 2 decisions. ↩︎

About that score: I use a system based on the Apache Voting System, which scores on a scale of +1/+0/-0/-1. In this case, +1 means particularly excellent, -1 means especially poor, and +0/-0 mean good or bad but in a fairly normal way. So the score here, “+0/+1” means “good, better than the average good answer, and verging on an exceptional answer.” But there’s nothing special about this particular scoring system; use anything you like. ↩︎