Making a Compelling Offer — in this economy?

This is an edited transcript of a talk I delivered at the CTOCraft Hiring MiniConf on May 31st, 2022. A video of my talk is also available.

This was the final talk in a conference that followed the hiring arc, from sourcing to interviewing to selection. So we’re finally at the end: covering making an offer that will be accepted. Which is probably harder than it’s ever been.

I want to start with a story, about a friend who I’m gonna call Phil. Not his real name; also, not a real picture – this is a stock photo.

Phil is someone I’ve known for most of my career. We’re about the same age, and at similar points in our careers. We have been working in various engineering and/or security roles for about 20 years. We talk very openly about money and compensation: we know a fair bit about what we each make (and could make). We’ve talked about different jobs together, and shared details of offers with each other.

Around the new year, Phil was considering new jobs. We had been chatting about it a bit, and he had been telling me about some of his offers.

Then, we had this (paraphrased) conversation:

![Those same two people talking, now with a text message conversation overlaid. It reads: 'I just got an offer from [Redacted] for $1.05 million. And turned it down. What is happening?'](/2022/jun/16/making-a-compelling-offer/slides/003.jpeg)

He had been offered a compensation package of over a million dollars … and he turned it down.

So, that’s what I want to talk about:

How do you make an offer that’ll be accepted when other companies are out there offering a million dollars?

Salaries have absolutely skyrocketed the last couple years, at least in the US1.

It’s not uncommon for even entry-level positions to see a six-figure offer. It’s pretty hard to hire a mid-career engineer, someone with 3-5 years of experience, for under $200,000. And we’re even seeing seven-figure offers like the one that my friend got. That’s still certainly an outlier, but not as much as they used to be. Seven-figure offers used to be pretty much reserved for senior executive or managing partner types of roles, but now we’re seeing them even for individual engineers and managers.

I’m operating under the assumption that most readers are not going to be able to offer at the very, very top of this inflated range.

So, how do you put together a compelling offer when you’re likely to be outbid?

I’m gonna cover three aspects that make a compelling offer:

- Cash

- The company culture.

- The benefits that you offer.

Whatever you’re going to end up offering, it’s important to be transparent about what your offer will look like up front.

Making someone sit through a long interview process just to offer them a package they were never going to take is a waste of their time (and yours). If you know that your offer might be less competitive, you need to tell people right away and give them the chance to drop out.

As an example, my current employer doesn’t do locality adjustment. We offer competitive salaries relative to the national average. But that’s going be more or less competitive against local offers depending on location. So, when I speak to a candidate from San Francisco, New York, Portland, etc., I have to make it clear up front that our offer is going to look not great compared to what you’re seeing locally. Candidates might decide that the other things we’re offering are worth the tradeoff, but they can’t make a decision there if I don’t give them all the facts.

The most important aspect of an offer is cash. There’s no getting around this. If you can afford to offer a seven-figure compensation package, you’re going to get nearly everyone you want!

But even if you can’t, you do need to be reasonably competitive. You need to know where you stand relative to the rest of the industry. You need to be making an offer that is within range of the other offers that people are looking at. If you’re dramatically below what is expected, candidates will think you haven’t done your homework, or that you’re trying to take advantage of them.

You should make sure you’re in range by looking at industry salary data. The best data I’m aware of comes from paid products like the Radford surveys.

If your company hasn’t bought a product like that, you can get there using the technique I blogged about last fall (salary data from levels.fyi, with locality adjustments from Robert Half).2

You also need to know what your organization’s pay bands are for the position – you need to know what your upper and lower bounds are, and how flexible you can be. (If you don’t have any pay bands: establish them before you list the job!)

After salary, the next most important factor candidates will use to select an employer is culture. Within roughly similar salary ranges, candidates will often choose based on the company that fits them the best. This is exactly what happened with my friend: he was being offered objectively great salaries. Even his “worst” offer was still pretty fantastic, so he was free to make choices based on other things. Usually “other things” is culture.

The important message I want to send about culture is: it doesn’t matter what you say about your culture; culture is what you do.

Throughout the whole hiring process, you’re demonstrating your culture through the details of the hiring process itself. Candidates will draw conclusions about your company culture based on what they see during the hiring process.

If you make them do silly exercises uncorrelated with work performance as part of the interview process, they’ll conclude that your company doesn’t know how to measure performance. If you’re bad at communication - if it takes you days to respond to their questions – they’ll conclude that your organization is bad at communication. If you show up late to interviews, that’ll conclude that you don’t prioritize being on time. If you schedule interviews very early or very late, or on weekends, they’ll conclude you don’t respect their free time.

Luckily we’ve just had an entire conference full of advice on making a kind, equitable and respectful interview process. If you don’t take the advice that you heard earlier today, it doesn’t matter how good your offer is.

There are no “hacks” at the offer stage that will make up for a poor candidate experience. Your offer begins when a candidate applies. If you want to make a compelling argument about company culture, demonstrate that culture throughout.

The last factor that candidates use to pick an employer is benefits.

Benefits are interesting. Good benefits can’t make up for low pay or a bad culture: you’re probably not going to convince someone to take a 50% pay cut because of your great free lunch.

But especially bad benefits can be a deal breaker. Healthcare is an example: I’ve had candidates who couldn’t apply for a job I was listing because they needed a specific insurer who wasn’t offered on our company’s healthcare plan.

And great benefits can sometimes be a deciding factor. If someone who plans to have kids is deciding between two similar jobs, one with fantastic parental leave and one without, the parental leave might be what pushes them in that direction3.

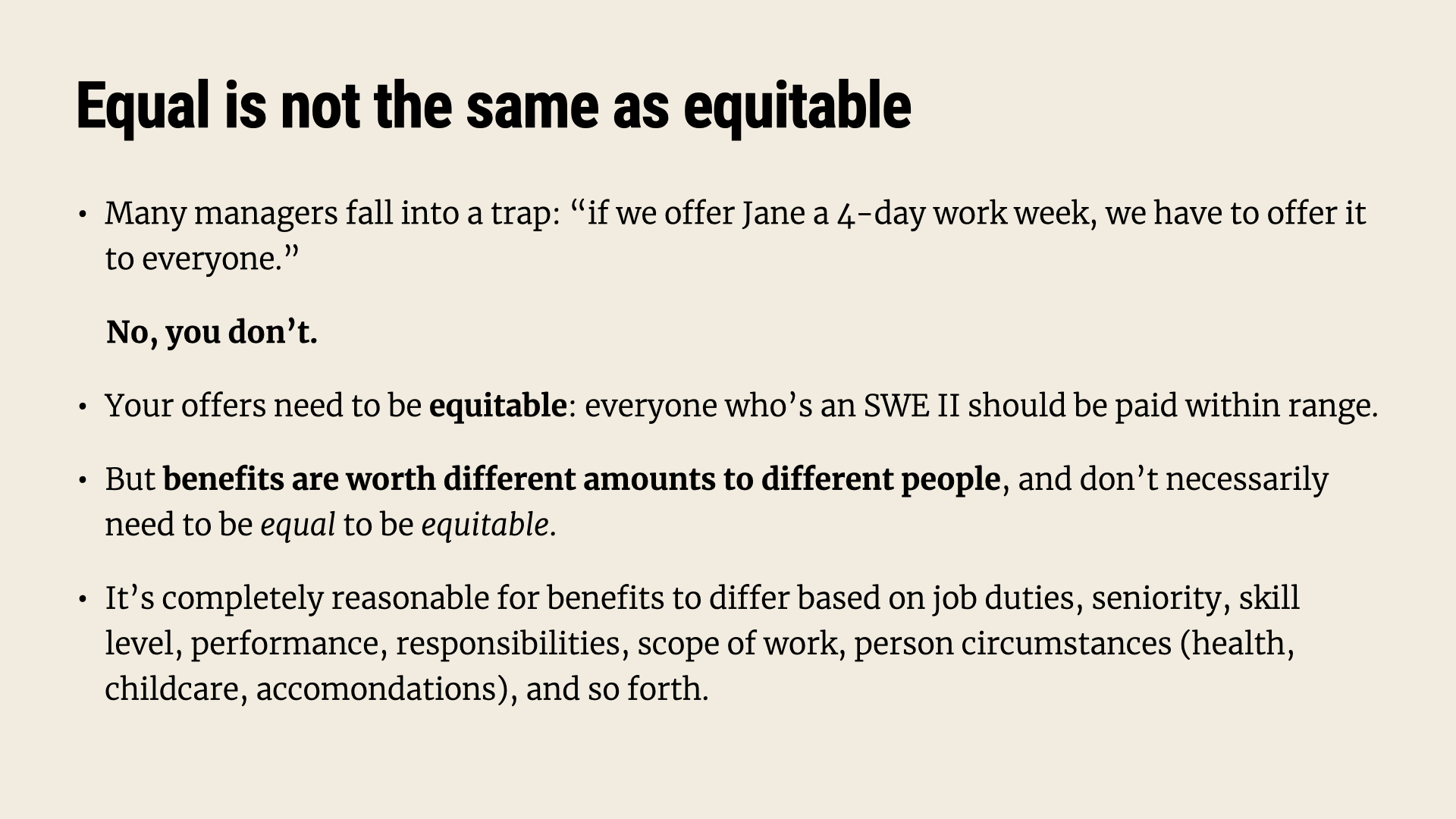

A trap people fall into when they’re thinking about benefits is how to offer benefits equitably. For example, imagine you’ve got someone who asks for a flexible schedule “hey, I want to take Fridays off, work a four-day week.”

Some managers think, “if I offer this to them, I have to offer this to everyone, and I can’t support a four-day work week for everyone, so I can’t offer it to anyone.”

That’s not the way it works. Equal is not the same as equitable. You don’t need to offer the same benefits to offer fair benefits.

You certainly need equity – everyone who is a software engineer II needs to be paid within the same pay range. But you don’t need to pay everyone the same salary: people’s compensation can differ based on their role and level4.

The same thing can is true of benefits. Not everyone needs to receive the same benefits, but you do need to have a fair and reasonable explanation for why certain benefits are offered in some circumstances and not others. It’s reasonable for benefits to differ based on job duties, seniority, scope of work, personal circumstances (either formal accommodations or not), and so forth.

And in fact, it’s good for benefits to be the place where people’s compensation differs widely. That’s because benefits are worth different things to different people! For me, time off is hugely important – I do better work when I have a good amount of time to not be working. I will almost always take a pay cut in exchange for more time off. But that’s not true for everyone else. If someone else is saving up for a down payment on a house, or trying to maximize their savings for retirement, they might prefer to sacrifice some days off in exchange for a higher salary. A hiring manager who wants to maximize their chances of success will learn these specifics, and tailor their job offers accordingly.

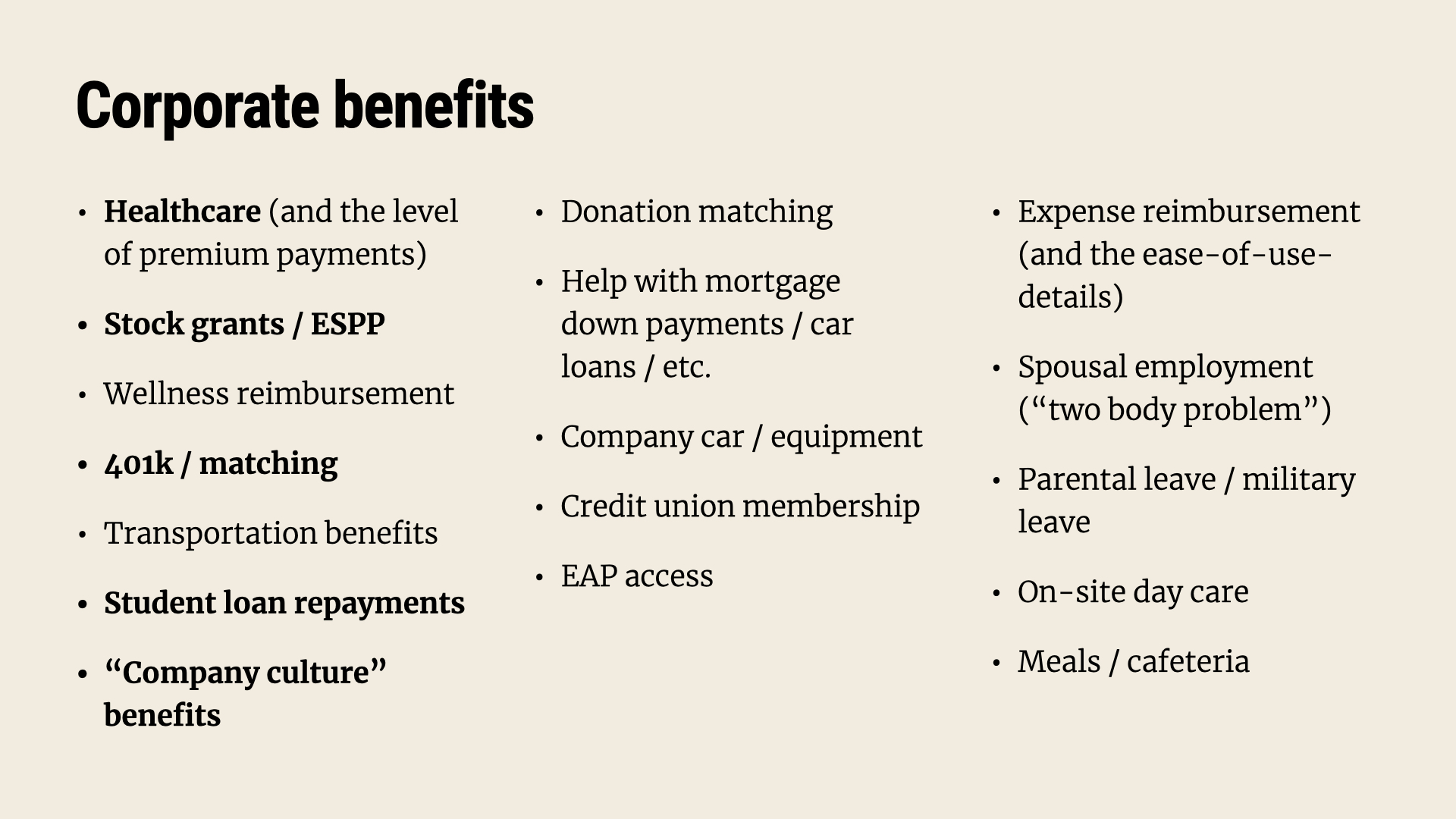

I think of benefits as falling into two categories.

The first is what I’m calling “corporate” benefits. These are the things that your HR department or your company is responsible for; to you, they’re fixed offerings that your company has or doesn’t have. These are even across all employees: you can’t offer one person a different healthcare plan than the rest of your company.

Unless you’re an owner or executive, you probably don’t have much direct control over corporate benefits. You probably can’t change your health care plan or your 401K match. But you should be aware of what you have, and where they stand relative to the industry. And if they’re bad, you should be pushing for an improvement over time as part of your long-term strategic hiring plan.

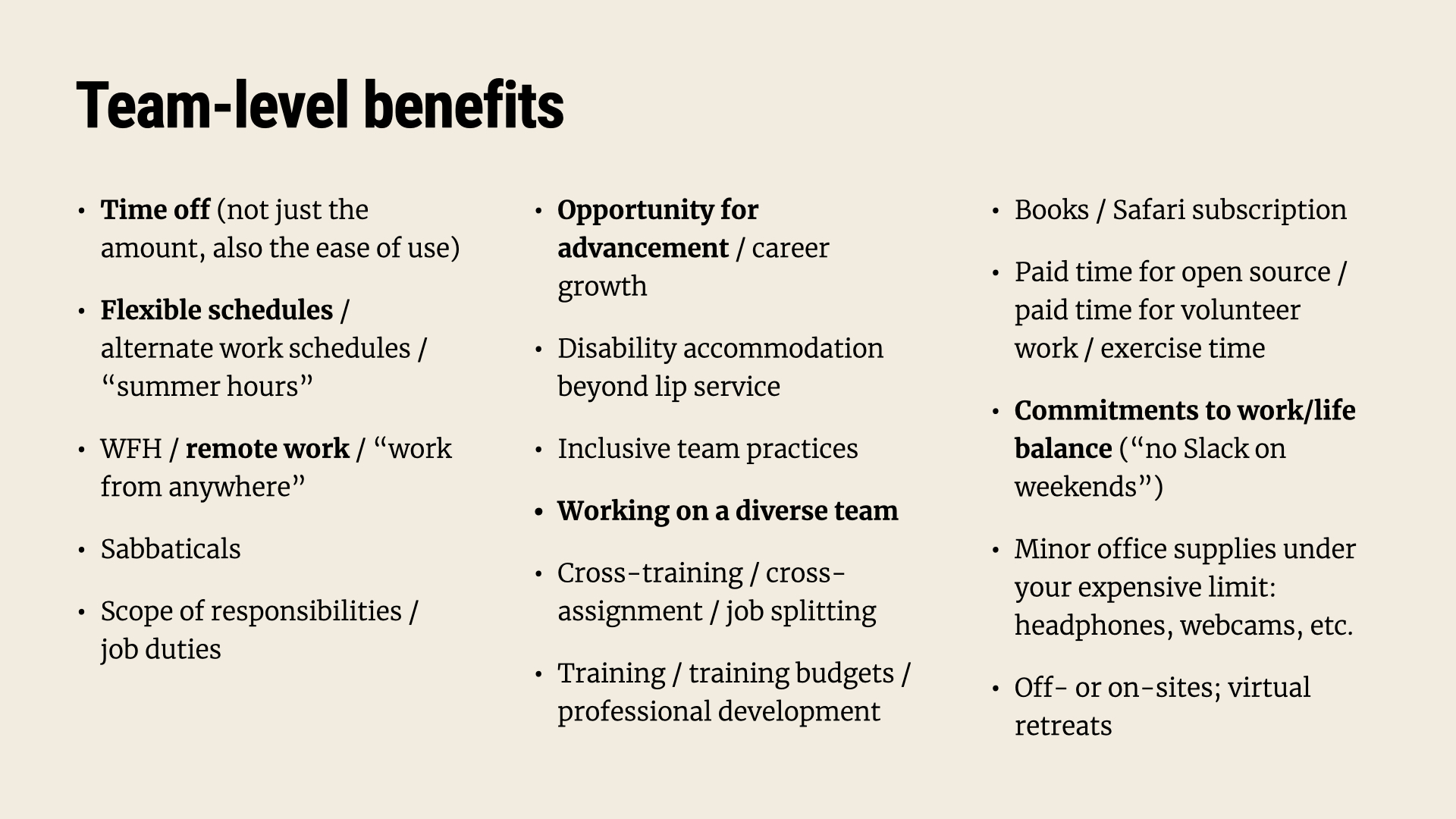

In contrast, there are other benefits that you probably do have more control over. I think of these as “team-level” benefits. These are offerings that differ from team to team, where you as a manager have the power to determine many of the specifics.

Many managers don’t realize this, but you have more power over these benefits than you might think.

You might think that time off is something set by the company, where you can’t be flexible and offer some people on your team more time off. Generally, that’s not as true as you might think: if you want to grant someone on your team more time off, it’s usually something your boss or HR will be happy to sign off on.

I encourage managers to think about their power as a manager along the lines of the reserved powers doctrine: any power company hasn’t explictly assigned to itself (e.g. HR) is implicitly a power you have. So if your company hasn’t said you can’t offer a flexible schedule, that implies that it’s on the table for you to offer, if you like.

You probably should read your boss in on any special deals you make, but you may not want to take it to HR. HR’s default is “equal”, rather than “equitable”. Start by asking your boss, and take “yes” for an answer.

Escalate if you must; this often is a hill worth dying on. As a manager, you’re going be judged based on the performance of your team. So, hiring the right person who’ll team perform is absolutely something worth fighting for.

In some circumstances, it might be worth making an under-the-table deal. If HR says “you can’t offer a four-day work week”, but that’s a dealbreaker for the person you want to hire, why not offer it anyway? It’s not the worst thing in the world to tell them, “look, this isn’t something we can officially offer, but if you just sort of don’t show up on Fridays, I won’t say anything.”

This is risky for you and even more so for your employee: under-the-table deals can change at any time, and can leave people feeling burned if not handled carefully. So if you’re going to do this, you need to be transparent about the fact that you’re being sneaky. But in certain circumstances, I think it’s OK. I’ve done it on occasion; I’ve been on both sides of an unofficial deal like this and it’s worked out. It’s worth considering.

Finally, let’s talk a bit about the logistics of making the offer.

Speed is essential. The candidate you love is interviewing elsewhere and could get another offer at any moment. In many cases, it’ll take some time to get a formal offer letter out. Don’t wait for that: send them an email immediately. As soon as you have made the decision – like within minutes of deciding you’ll make an offer’ – let them know.

This is why you need a comprehensive understanding of pay and benefits: if you don’t, you’ll need to wait for the formal offer letter. But if you do, you can send your candidate an informal pre-offer. I’d suggest sending an email that says “we’re going to make you an offer, and here are the general details: …” That way you can begin negotiating ahead of any formal offers, and not waste any time.

Email is just fine here. There’s outdated advice floating around there that says offers should only be given over the phone. Ignore it, just send an email.

As you put together the offer, don’t play games. Make the best offer you possibly can. This isn’t the time to try to save a few bucks out of your budget. You have a salary range for the role, and your interview will have established where the candidate falls within that role. If they’re at the top end of your skill requirements, make them an offer at the top end of the range. This isn’t like buying a car; you don’t need to open with a low offer to try to get a deal. You should open with the most compelling offer you think you can make.

This is advice usually given to candidates, but it applies to hiring managers as well.

Remember that, when you’re negotiating, you’re negotiating the entire package. It’s easy to get caught going back and forth on a single number (usually the base salary). If a candidate asks for a base that’s out of range for your salary bands, don’t just say “no”; offer something else. This might sound something like:

Unfortunately, the top of our pay scale for this role is $150k; I can’t up to $175k like you asked. However, I remember you saying that getting to go to conferences was important to you; how about we try to make up the difference by sending you to a bunch of conferences as part of your job duties?

You should expect negotiation, and be gracious about it. Remember that strong candidates will have multiple offers; if you’re a jerk when someone counters, they’ll go elsewhere. Or, you’ll poison the well for your future relationship with this person.

It’s just business; don’t take negotiation personally. Be kind and gracious, and if you can’t come to terms thank them very warmly and wish them luck! You never know when you’ll encounter this person again Even if you never do, it’s never wrong to be kind.

Good luck out there! I’d be happy to answer questions about this – or anything I write – over email or Twitter.

I think this is starting to pause a little bit with the developing recession, but I don’t expect much of a correction, maybe just a slowing-down of the increase. ↩︎

I think these resources only apply to United States employers. I don’t know enough about talent markets outside the US to have great advice/resources there. ↩︎

Parental leave is also one of those benefits that communicates something about the company culture. I don’t plan to have children, but I still look for companies with strong parental leave policies: they tell me that the company believes that people have lives outside work, and is happy to support them. ↩︎

That said: check out what Oxide is doing. ↩︎