If we had $1,000,000…

A couple weeks ago I gave a talk at DjangoCon US about the finances of the Django Software Foundation. I wanted to give folks a high-level understanding of our current financial situation, and then imagine a world where we had a substantially-larger budget.

Once the video’s available (which should be any day now), I’ll post it here. Below, you can find a written version, with annotated slides and expanded notes.

You may also be interested in turning a conference talk into a blog post, the technical notes on how I turned the presentation into this post.

Outline:

- The DSF’s budget today

- What if we quadrupled it?

- How do we get there?

- Calls to action - how you can help

- What do you think?

Howdy, folks. I’m Jacob. I’m on the board of the Django Software Foundation, and I’m our Treasurer.

This talk today has three parts. I’m going to talk about the DSF’s budget, what it looks like today, where our money comes from, how we spend it. I’m going to imagine a world in which that budget magically gets quadrupled, and suddenly we have a million dollars to play with. What might we do? And I’m going to talk about what we might be able to do to get from here to there. There’s also a secret fourth part to this talk, but we’ll get to that.

The DSF’s budget today

What does our budget look like today?

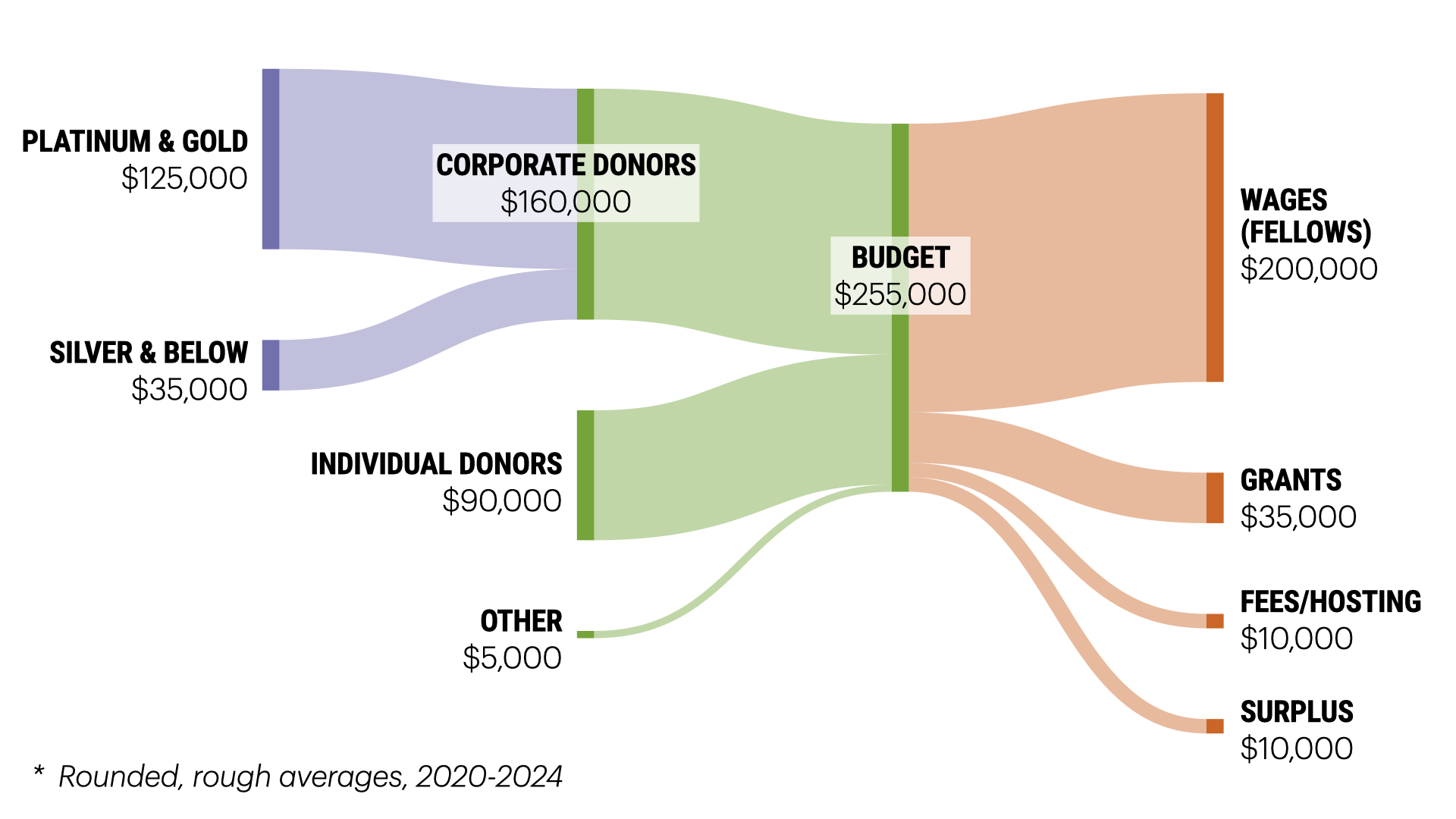

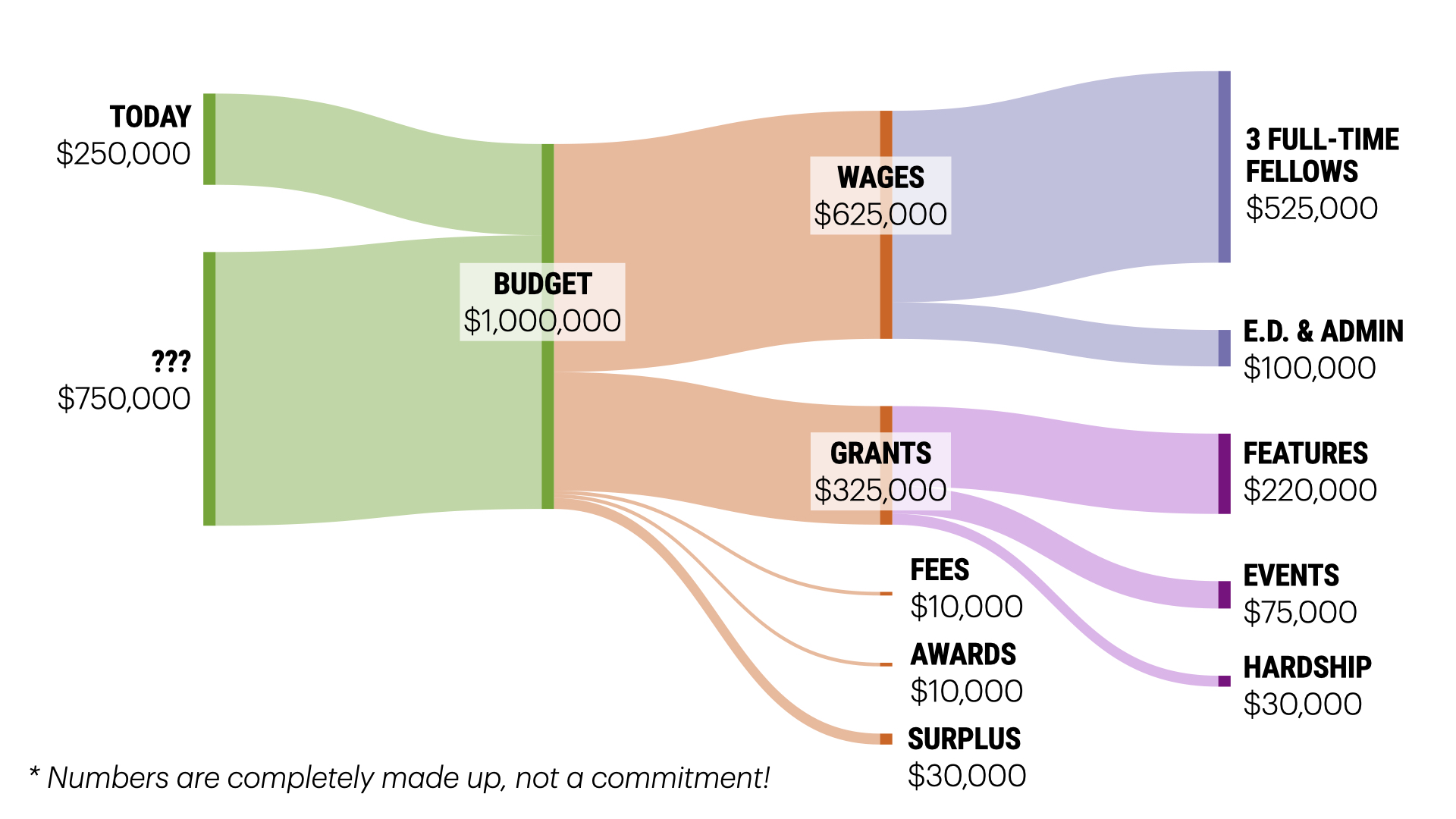

This is a visualization of our finances as they stand today. This is a rough, simplified average — not exact — of what our cash flow looks like over the last five years (2024 is an estimate). It’s fairly accurate, but it’s not really intended to give you a down-to-the-dollar accounting. It’s more intended to give you a broad understanding of where the money comes from and where it goes.

So where does the money come from?

- Corporate sponsors: mostly large donations measured in the hundreds or in the thousands of dollars per year. Most of these donations come from our top-tier Platinum and Gold sponsors.

- Individual donations: we also get about $90,000 a year in small individual donations. These are around $5, $20, sometimes up to $100 a year, but quite small.

So where do we spent that money?

We spend the bulk of our money paying people. So that’s our Fellows, Natalia Bidart and Sarah Boyce, and also our board admin, Catherine Holmes. The way I think of this: we spend most of our money paying people to keep the project and the foundation healthy. Fellows triage tickets, review pull requests, and otherwise keep development flowing smoothly; our board admin keeps our books, helps the board stay organized, works with sponsors and grant recipients to move money, and otherwise keeps the foundation moving smoothly.

We also issue grants: about $35,000 a year on average. These go mostly to events, ranging from small single-day events like DjangoGirls workshops, to large conferences like DjangoCon US/DjangoCon EU/DjangoCon Africa/etc.

What if we quadrupled it?

Now let’s imagine a one million dollar budget…

Why that number? Well, partially because it’s nice and round number, and partially because it’s a convenient four times our current budget. But also it’s a very achievable number — there are companies in our community who could give us a million dollars today without much impact on their bottom line. It’s not a number that’s particularly ridiculous in the scope of the amount of money that’s being made with Django; I think we could get there.

At this point I should clarify – I’m speaking personally, not for the DSF. I think many of these ideas would be broadly supported by the DSF board – I don’t think I’m proposing anything particularly controversial – but ultimately this is just my opinion, not any sort of consensus view or actual plan. If someone were to give us a million dollars today, I can’t promise that we would spend it like this specifically. But my guess is that would probably look somewhat similar to what I’m about to propose.

My wishlist for a $1 million budget

So what’s my vision for a one million dollar DSF budget?

Hire an executive director. Currently, the DSF employs a few people, but none of the leadership is paid — it’s an all-volunteer board. We have reached the limit of what a volunteer board can do; I can’t imagine effectively spending four times our budget without someone whose full-time job it was to do that ethically and effectively. I certainly can’t imagine raising a million dollars without someone whose job it was to manage fundraising efforts. I just can’t imagine a world in which we get to this point without a professional working on the project; I’ll talk more about this later.

Expand the fellowship program. The Fellowship program has been hugely successful and one of the secrets to Django’s stability and longevity.Right now we have one and a half Fellows – one full-time, and one part-time. They are also at the limit of what they have time for; there’s more than enough work to justify more Fellows. I think we could easily employ three full-time Fellows — essentially be doubling our Fellowship size.

Maybe the most controversial thing in this talk: one of the things I would want to see us do with that extra Fellow time is reconsider our policy that “fellows don’t work on features”. This is a much bigger discussion that I can do justice to right now, so rather than make a strong case I’ll just say: with more money, it’s possible — if we want to.

- Expand the grants program. Finally, we could dramatically increase our grants budget – by nearly ten times. This would come in three parts:

- More and larger event grants. I’ve heard from several grant recipients that they were disappointed with the size of their grants. That sucks: I wish we could give everyone what they ask for — and more.

- Feature grants: imagine if you had an idea for something that should be part of Django or a really compelling third-party package, but needed funding to get it done. Imagine if the DSF could fund that work. This would sort of be like a fourth Fellowship role, but one that would float around to different people as they had different ideas and different things they wanted to implement.

- Hardship grants, an idea borrowed from the Rust Foundation. The Rust Foundation issues grants to people in their community experiencing some sort of financial hardship. So if you’re a member of the Rust community and you’ve lost your job, are struggling to pay for medical expenses, etc., you can apply for a grant and the Rust Foundation will help you out. What an incredible example of caring for your community! After all, what are foundations like the Rust Foundation or the DSF for, if not to care for their communities? I’d love to implement something like this.

Here’s a way to visualize what this million dollar budget might look like. We’d still be spending the bulk of our money on people — close to three quarters of that budget would go towards wages. That’s simply taking what’s worked and doing more of it. We could dramatically expand our grants budget, spending close to our current budget just in feature grants, and more than tripling our event grants budget. With a million bucks we could do quite a bit!

How do we get there?

Now, you may notice that this chart is remarkably vague about where the other $750,000 comes from – so let’s talk about that.

Major donors vs many-small-funders

Broadly speaking, there are two ways that nonprofits raise money: they can raise money from major donors — just a few very large donations — or they can gather lots of small donations from many small funders.

Sue Gardner wrote about this strategy decision when she was the executive director of the Wikimedia foundation. She writes that:

[D]onors rarely experience the core mission work first-hand — most people who donate to Médecins Sans Frontières [(Doctors Without Boarders)], for example, have never lived in a war zone. That means that most, or often all, the actual experiences a donor has with a nonprofit are related to fundraising, which means that over time many nonprofits have learned that the donating process needs –in and of itself– to provide a satisfying experience for the donor. All sorts of energy is therefore dedicated towards making it exactly that: donors get glossy newsletters of thanks, there are gala dinners, they are elaborately consulted on a variety of issues, and so forth. […] So. A major structural flaw of many nonprofits is that their revenue is decoupled from mission work, which pushes them to focus on providing a positive donor experience often at the expense of doing their core work. That’s bad.

Because of this, the Wikimedia Foundation developed a strategy to raise money from many small donors:

[We] picked many-small-donors, because we felt like it was the revenue model that best aligned with our core mission work.

Today, the WMF makes about 95% of its money from the many-small-donors model — ordinary people from all over the world, giving an average of $25 each.

It’s awesome.

We don’t give board seats in exchange for cash. Foundations’ priorities don’t override our own. We don’t stage fancy donor parties (well, we do stage one a year, but it’s not very fancy), and people who donated lots of money have no more influence than people who donate small amounts — and, importantly, no more influence than Wikipedia editors.

This certainly sounds attractive! Could we make it work?

Maybe! Our community is certainly big enough. Django is downloaded around 3 million times a year (by real people, not automated builds). So if pip install Django charged you 33¢, there’s you go. I think most of you would probably pay 33¢ a year for Django — certainly doesn’t seem like a lot of money.

This is of course a silly example, but the point is — there are plenty of people who use Django, and it’s quite possible to imagine small donations adding up.

However, I think it would take being much more aggressive about grassroots funding. Everyone gets annoyed at funding drives — but these aggressive fundraising tactics work. There’s a reason why organizations use them.

If the DSF was serious about a small donor’s strategy, you would see my ugly face on the home page of djangoproject.com a lot. Realistically, I don’t think that’s something we want to do as a community. I think the kind of pushy fundraising we’d need to do to raise one million through a small donor strategy probably isn’t something the community would find palatable.

But I think that’s probably okay. To come back to the incentives that Gardner talks about: we’re different from Médecins Sans Frontières in that the companies that make up our major donors do experience the direct benefit of our foundation’s work. Look at the sponsor banners around this conference: these are organizations that have built businesses and hired people and been successful because of Django. They are experiencing the benefit directly. So we don’t have the same perverse incentives — or at least, not as strongly.

And the major donors model has the advantage of probably being easier. It’s far easier for me to picture convincing eight or ten or fifteen large companies to make large donations than it is to picture increasing our small donor base tenfold. So I think a major donor strategy is probably the most realistic one for us.

How do we approach major donors?

So when I talk about major donors, who am I talking about? I’m talking about four major categories: large corporations, high net worth individuals (very wealthy people), grants from governments (e.g. the Sovereign Tech Fund run out of Germany), and private foundations (e.g. the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative, who’s given grants to the PSF in the past).

But how do you get these major donors to give you large sums of money? It’s a skill! Working with large donors is not something I know how to do; it’s probably not something that most software developers know how to do. That’s not because it’s magic, any more than building a Django site is magic. The work we do seems like magic to people who haven’t learned it, but it’s not; it’s a skill we’ve developed. Well, there are people who’ve developed the skill of working with major donors, and they do it really effectively. One of the reasons that the DSF’s budget is as small as it is that, well, we’re not particularly great at fundraising! We’re getting amateur results because… we’re amateurs. So, this brings us back to hiring an executive director. Once again: we should hire experts and pay them to do their job. It’s worked really well for us in other areas, and it can work well here.

I should point out: focusing on major donors doesn’t mean ignoring small donors. The types of programs you need to develop for major donors - transparency about spending, sponsorship prospectuses, that sort of stuff — also helps attract smaller individual donors. I would expect that any competent ED would actually pursue BOTH strategies.

Calls to action - how you can help

So here’s the secret part four to this talk: how you can help. Yes, I’m going to ask you for money — but not just money. In fact, I’m mostly not going to ask you for money; what I’m asking for is probably harder.

I’m going to break this up into three ways you can help achieve this vision, or one like it: Easy things, things that you can do in a few minutes; medium things that might be more difficult; and some high-achiever stuff.

Easy

If you’ve contributed in any significant way to the Django community, you are eligible to join the Django Software Foundation as an individual member. This means volunteering at a conference; writing blog posts or publishing YouTube videos about Django; contributing code or documentation to Django, or a third-party package; and so forth. Joining the DSF gives you a voice in further decisions, and the right to vote for the Board and the Steering Council. If you are someone who has contributed in some way to Django’s mission, consider joining the DSF.

If you can afford to, please make a donation directly or via github. If you can’t afford it, please don’t. I don’t want you to give us money if that’s taking away from your ability to pay for rent or your own financial security. But if you can afford even a few bucks a month, you should donate. It is important, even with major donors, to have broad grassroots support. The number of individual donors helps emphasize the health of an organization. So your donation helps us explain to other donors that we’re not just some fly-by-night organization, but we have thousands of people who donate and support us. Even just a couple of bucks is meaningful.

If you can afford to donate but don’t want to for some reason, tell me why. Even if it’s critical. Especially if it’s critical. Honestly, this might be more valuable to us as a project than a donation! Understanding what we could be doing differently to attract more donors is super valuable.

Finally, buy PyCharm during their “support the DSF” promotion. I mentioned the importance of our large donors - JetBrains is one of those, this promotion is how they support us. During this campaign, you get a discount and every dollar goes to the DSF. It’s a total win-win and it’s one of our major sources of funding. So if you are thinking about buying PyCharm, now’s the time to do it.

Medium

- Ask your company to become a corporate member of the DSF. I suggest asking your company for around 1% of your company’s annual revenue. That’s a big number for us but a small number for them. I’m guessing most companies will probably say no — and if they do, tell me about it. Once again, hearing directly about the barriers to contribution would be super helpful.

- If you are doing estate planning, did you know you can include the Django Software Foundation in your will? If you can’t afford to make a donation now, perhaps you can leave something to us in your estate.

- If you are a high net worth individual, consider making a large donation yourself. And once again, if you could, but you don’t think that’s the best use of your philanthropic money — that’s fine, but I would love to understand why; get in touch.

- Finally, if you can’t do any of this stuff personally, but you think you know some people who can, introduce me to them. Let me see if I can help facilitate something.

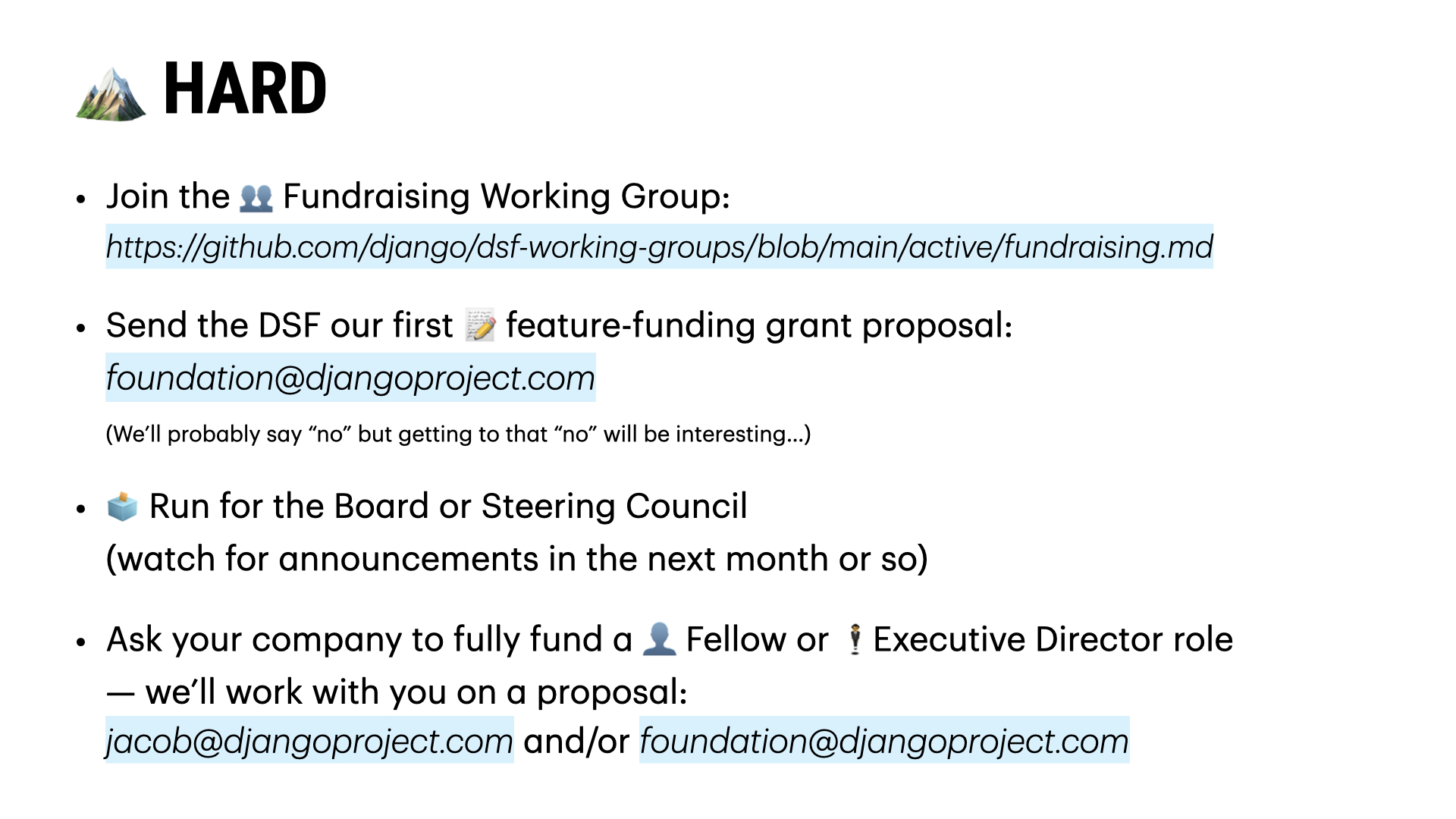

Hard

Finally, some hard stuff, for the overachievers in the room:

- Join the fundraising working group. We have a working group at the DSF that focuses on fundraising. It’s new, just getting started, but this is where the discussions about fundraising are centered at the DSF for now. Anyone’s eligible to join, member or not.

- I would love for someone to send the DSF a feature grant proposal. We don’t have a feature grant program now; we have never given a feature grant in the past. So we’ll probably refuse your proposal, but, man, I would love to have that conversation as a board. You would be doing us a great service whether or not we said yes.

- Consider running for the Board or for the Steering Council. The board leads the DSF. The steering council leads the technical development. Board nominations are open now; there will likely be a Steering Council election in the coming months. Feel free to reach out to me if you have questions about either of those.

- Finally, we’d love to work with an organization that likes this mission and wants to help us get there more quickly. We can work with a sponsor who’s particularly interested in some specific role and fully fund one of these ideas, one of these positions. This is probably the most realistic way of bootstrapping from where we are today to where we want to be — find a supporter (or a few supporters) who’ll directly fund us to take the next step. We’d love to work on a proposal collaboratively; get in touch

What do you think?

I hope this gets y’all excited about where we could go — let’s make this happen!

I’m very serious about wanting to hear from you about any or all of this. I read every email or other message I get, and I answer nearly all of them (eventually). Please get in touch.