Sidebar #3: Two Flavors of Medium Risk

This is the fifth part of my series on thinking about risk, and the third “sidebar” to part 1, my basic introduction to risk. It’ll make the most sense if you’ve read that piece and understand the terms risk, likelihood, and impact that I discussed there.

Medium ≠ Medium

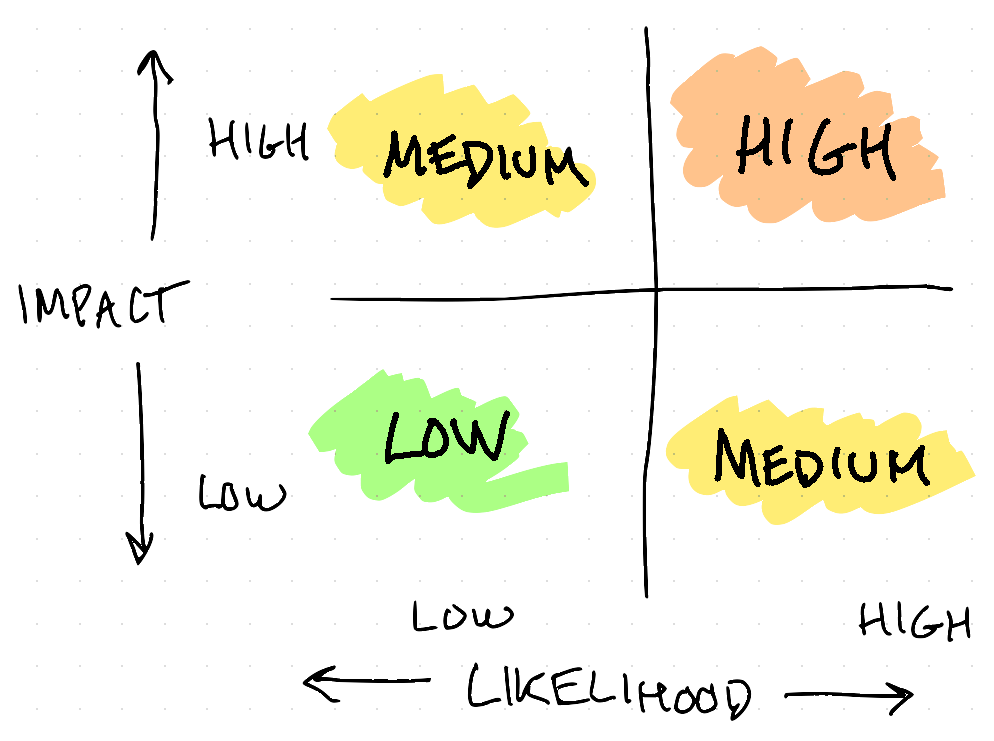

Let’s take another look at the simplest risk matrix from Part 1:

Notice that “medium” is on there twice – and they’re not the same! These are two very different “flavors” of “medium risk”. In the first, you’re likely to mess up, but unlikely to face serious consequences; in the second, you’re unlikely to mess up, but if you do, the outcome is tragic. Collapsing these both under “medium” risk is a dangerous oversimplification.

This is most clearly explained in a post by the explorer and wilderness educator Luc Mehl, Highly likely, low consequence: The learning sweet spot. Luc points out that the low-likelihood, low-consequence zone

… fits events that are not likely, and not a big deal, like a flat tire on a bike when commuting to work. This is a comfort zone, and we don’t learn much here.

However, that high-likelihood, low-impact zone is “the sweet spot for learning”:

Events [in that zone] are highly likely, but not a big deal. Most of my work as an outside educator is in identifying or creating those sites: where can we fall out of our boats, intentionally trigger weak layers in snow, or learn about the different ways that ice crack, with as much margin of safety as possible?

That “flavor” of “medium risk” stands in stark contrast to the other corner of “medium risk”,

… where events are not likely, but have high consequences. This corner terrifies me.

It terrifies me too! Low-likelihood/high-consequence scenarios are very difficult to reason about, very difficult to understand if we’re making prudent decisions. This is one reason I include “where did we get lucky?” in my retrospective practice – it can help me tell the difference between taking an appropriate risk versus a situation that could have ended quite terribly.

There are two important lessons that flow from understanding these two different flavors of “medium”:

Communicate existential threats differently, even low-probability ones

Most broadly, these two flavors of “medium” point to one of the major challenges of risk communication. I’ve struggled with this often in my career: how do you properly communicate something like “there’s a 1% chance of a breach so bad it puts us out of business”? That’s a very different scenario from “there’s a 50% chance of an outage lasting a day” – but both scenarios end up with a “medium” label.

This isn’t just a problem with qualitative risk labelling; it can be a problem with some forms of quantitative risk analysis too. Saying “$1,000 of risk” isn’t any more helpful than “medium”; it still doesn’t say if this is a high chance of low impact, or a low chance of high impact. Even with quantitative risk measurement techniques, you have to go farther than just multiplying. I’ll talk about this more in the next article, which revisits quantitative risk measurement.

My favorite simple technique is to steal a page from wilderness medicine. In wilderness medicine scenarios, we treat “threats to life and limb” — injuries that could lead to loss of life, or major functional loss — as substantially different scenarios from all other situations. We evacuate sooner and more rapidly, we’re more willing to try high-risk evacuations (i.e. helicopters) – we don’t mess around with these scenarios.

In the same way, in engineering contexts I find it useful to explicitly call out existential threats as something distinct from other scenarios. Instead of “doing the math”, I’ll say something like “this scenario is super-unlikely, we think less than a 1% chance, but if it does happen we’ll go bankrupt”. It’s important, when dealing with existential threats, that everyone understands the nature of the risk.

Spend as much time in “the sweet spot for learning” as possible

On the other side of “medium”: we should try to spend as much time as possible in that “sweet spot for learning” – high probability, low impact – as possible. Messing around in environments where it’s safe to make mistakes is such a good way to learn!

We tend to do this well in wilderness contexts – we practice climbing in gyms, ski in resorts where avalanche danger is managed away, take practice “shakedown” trips with new gear before relying on it in higher-consequence endeavors, and so one.

But I think we’re actually pretty bad at this in information security and engineering contexts. We tend to treat security/operational incidents as things to be avoided, and therefore often get caught flat-footed when a serious incident occurs. One of the most important things you can do if you’re trying to get your organization to manage risk better is to find as many opportunities to hang out in this learning zone as possible.

Here are some ideas for getting into the learning zone in a security/engineering context:

- Tabletop exercises. These are a bit like a role-playing game: have people pretend that there’s been an incident, and walk through, with them, the steps they’d take.

- Penetration tests - contracting “red teams” (or staffing them internally) to try to break your systems are a great way to experience a real breach without the consequences of real threat actors.

- Bug bounties are essentially large-scale, ongoing, high-likelihood/low-consequence exercises.

- Simulated outages, e.g. deliberately taking down a database leader to see if failover to a follower happens correctly. (Aka chaos engineering.)

It can often be difficult to convince leadership to tolerate these sorts of activities – “you want to deliberately crash our database during business hours!?” – but I’ve found using this high-likelihood/low-consequence framing helps. In particular, leadership is often receptive to the idea of tolerating a small amount of risk now to mitigate a much larger future risk.

You can find all posts in this series here and follow me in various ways. And if you’ve got questions, or topics you’d like to see covered in this series, please get in touch.