3d printed parts have different strength characteristics than conventionally-manufactured parts

An interesting 3d printing lesson about how the physical characteristics of printed parts differ from other manufacturing:

I needed to replace a rubber hydraulic hose retention strap on my tractor. The part’s $40 + shipping – ludicrous for a 6x2" strip of rubber – so perfect to try to replicate. I have some TPU filament that’s of similar flexibility, let’s go.

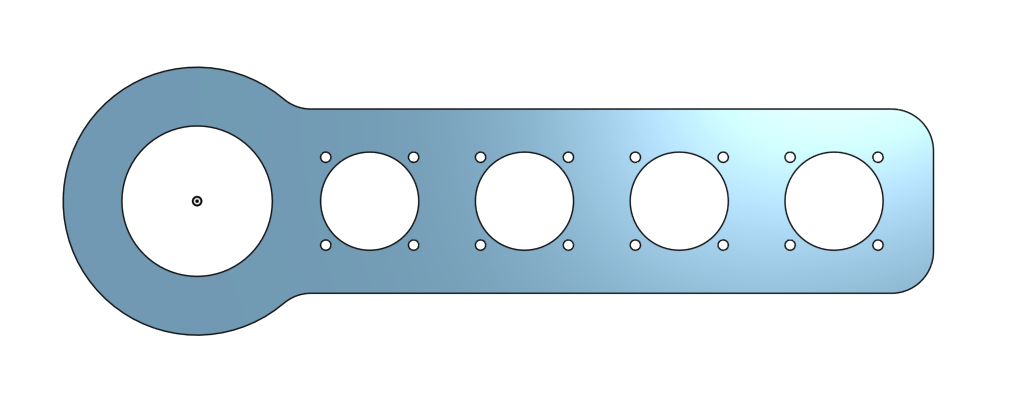

For V1, I just replicated the geometry exactly - including, without thinking about it, some little relief holes around the main hose holes:

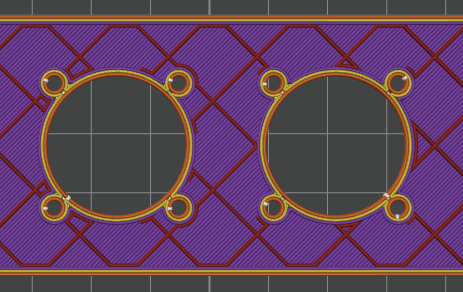

In the original rubber part, these holes serve to weaken the rubber around the hose holes, allowing the strap to be stretch around the hoses. But 3D printing is different: 3d printed parts make a few solid permitter loops around the outside edges of the part, and then weaker sparse patterned “infill” around the rest of the part:

Thus, in the 3d printed part, these holes actually make the part stronger in those areas — precisely the opposite from the conventionally-manufactured rubber original. Oops!

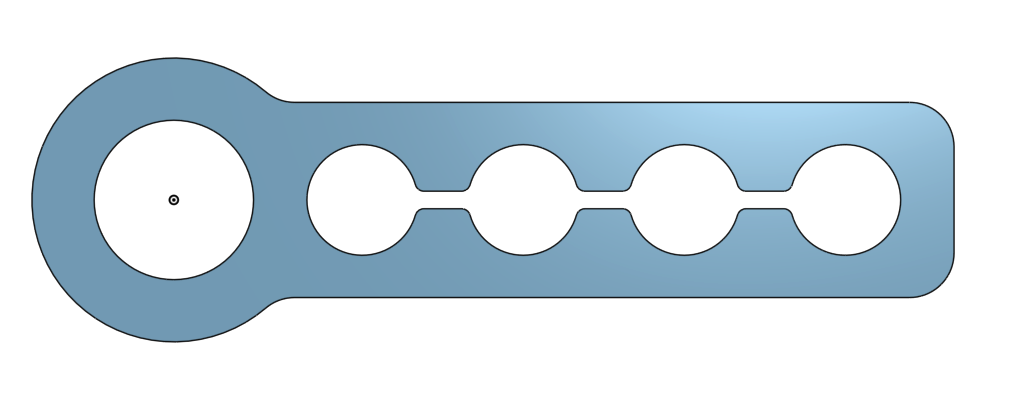

The fix was to weaken those holes in a different way more suitable to 3d printing:

(I also used the “grid” infill patterns, on the suggestion of a friend, because it’s weaker in the vertical direction and thus allows the part to flex a bit more than other infill patterns that are designed to be strong in all three dimensions.)